Intervju av David Larsson

Victoria McCarthy

“- On a general level, I am interested in the element lithium due to its relevance for the upcoming ‘green’ transition as it is the most efficient and light material for the construction of electric batteries. On this note, even though lithium batteries represent the best hope for many, to me it is also the embodiment of neo-extractive models, which basically means that under the veil of ‘green’ energies, land and people in the Global South are exploited for the benefit of the Global North.”

- Victoria McCarthy

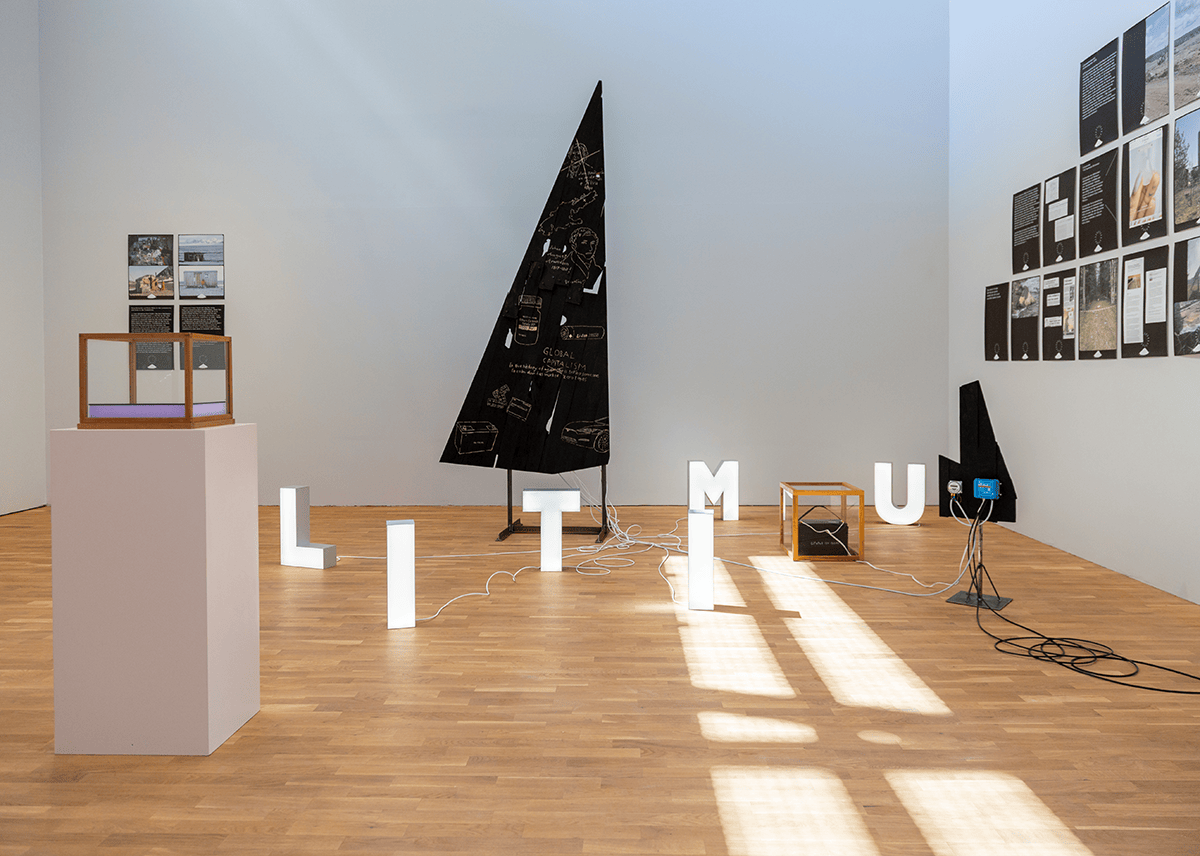

I met Victoria McCarthy for the first time on a field trip to Utö, the island in Stockholm archipelago where lithium was first discovered more than 200 years ago. The study trip was co-arranged by IASPIS and me following the opening of the exhibition Lithium Time in Haninge Konsthall. Victoria McCarthy, at that time a student at the Curating Art Program at Stockholm University, was doing her internship at IASPIS and came along for the trip. I remember us walking through the forest on Utö talking about the fact that her home country Argentina holds the world's second largest lithium reserve in the world and is a major player in the growing global lithium market. Lithium that gets extracted in Argentina is exported and ends up in batteries in electric cars in Europe and the US - from the Global South to the Global North.

Since this interview is part of a collaboration between Nya nya Norrland and Lithium Time – two art projects situated in Sweden and the Global North – it might be worth noticing that this division between North and South is at play also on a national level in Sweden, but here somehow in the opposite direction. The division between a Global South and a Global North is not only a geographical division but it also follows along the same lines as historical colonial structures,evoking some of the ideological notions that are underlying colonialism. In short, that the North is more “developed” than the South, and thus have the “right” to use the Global South as an extraction zone for raw materials that are wanted in the North. In Sweden these geo-cultural categories exist in a similar way but geographically inverted. In Sweden, the North is where the extraction takes place and the South is where the wealth is being accumulated. In other words, the Swedish North has been colonized by the South. The north has been (and still is) a place for extraction of resources as well as a place where the indigenous Sami population has been forced to relocate to give room for mines and water power dams and to adapt to the hegemonic Swedish language and culture.

In January, a year after our trip to Utö, Victoria publishes her master thesis Seeing Lithium Extraction: Countering the Myth of ‘Green’ Transition through Contemporary Art and in the introduction she writes about the Utö field trip as one of her starting points in thinking about lithium in relation to contemporary art. Later in the spring she organized a film program and a symposium at Färgfabriken in Stockholm where I was invited as one of the speakers. In the beginning of the summer I reached out to Victoria to continue our conversation and to hear some more of her thoughts around lithium, extraction practices, the so-called “green energy transition” and what, if anything, contemporary art has to offer in this context. How did she become interested in lithium in connection to contemporary art?

![Victoria McCarthy at Utö during Litiumtidens festival]()

You were saying that in Argentina there is quite a lot of media coverage around lithium extraction and the lithium industry, in Sweden my impression is that it is mostly written about in specialized journals on finance and/or mining. How have you experienced the public understanding around lithium in Sweden?

This is really interesting to hear, and I have had similar experiences when talking about lithium to people in Sweden. But on the other hand, as you say electric cars are very common here and there are also several large battery factories being built at the moment, so one could think that the general knowledge would be better?

Something that is quite striking when one starts to look into the media coverage around lithium is that one story is repeated over and over again in western media: it is the story of Lithium as the “white gold” that will replace oil and coal as fuel in the vehicles of the future. And the story is always illustrated with stunning photographs from the Andean salt flats in Argentina, Chile or Bolivia. Something white, pure, clean and beautiful to replace the black, greasy, dirty and ugly oil and coal industry while at the same time make the connection to gold and the gold rush as the original story of literally digging up treasures from the earth. It is much rarer to find stories in the media that talk about the ecological problems and social injustices that occur in and around the extraction zones or stories that try to problematize this absurd idea that we as a society could somehow mine, produce and consume ourselves out of the global climate crisis. And so while literally all of us carry around one or more lithium batteries in our pockets at all times (in our phones, earplugs, power banks, computers, tablets etc.) most people are completely unaware of the implications that lithium extraction, refinement and battery production causes around the world. During the time that you have been interested in lithium have you noticed any change in the general discourse when it comes to awareness, knowledge or interest around lithium?

For me the two things that stood out in the seminar at Färgfabriken, which is maybe also the two things that I find most alive in my own thinking around lithium is that the “new” structures around lithium extraction follow in more or less exactly the same lines as the historical colonialist and extractivist practices of the past, but at the same time and due to the ongoing climate crisis we still somehow have to do it…

This is a very interesting thought, to try to challenge the language and charge this necessary transition with other values. I have been thinking a lot around two specific perspectives on the global situation: the group that call themselves Ecomodernists and on the other hand the degrowth movement. Both of these groups agree that we have a climate crisis and that global action is necessary but they disagree on what this action should be. The Ecomodernists claim that technological solutions, including nuclear energy and carbon capture can “decouple economic growth and ecological impact” and thus “save the climate” while continuing with economic growth. The Degrowth movement, as the name suggests, makes the claim that the only way to “save the climate” is to radically reduce global production and consumption and thus enter an era of decreasing economic growth. I think that maybe one single perspective can never be enough but that we need to keep many, and sometimes contradictory thoughts in our heads at the same time. Changing what language we use to describe both the problem and the possible solutions is then probably an important and quite powerful tool.

You wrote your thesis around lithium in contemporary art and you curated a video program, as well as a symposium on Färgfabriken based on that research. What is the next step in your practice and will you continue working with lithium as a thematic for your coming projects?

That sounds like a great starting point for an exhibition, I am really looking forward to seeing that and to follow what you are up to and how your thoughts develop going forward. Thank you for taking the time.

Since this interview is part of a collaboration between Nya nya Norrland and Lithium Time – two art projects situated in Sweden and the Global North – it might be worth noticing that this division between North and South is at play also on a national level in Sweden, but here somehow in the opposite direction. The division between a Global South and a Global North is not only a geographical division but it also follows along the same lines as historical colonial structures,evoking some of the ideological notions that are underlying colonialism. In short, that the North is more “developed” than the South, and thus have the “right” to use the Global South as an extraction zone for raw materials that are wanted in the North. In Sweden these geo-cultural categories exist in a similar way but geographically inverted. In Sweden, the North is where the extraction takes place and the South is where the wealth is being accumulated. In other words, the Swedish North has been colonized by the South. The north has been (and still is) a place for extraction of resources as well as a place where the indigenous Sami population has been forced to relocate to give room for mines and water power dams and to adapt to the hegemonic Swedish language and culture.

In January, a year after our trip to Utö, Victoria publishes her master thesis Seeing Lithium Extraction: Countering the Myth of ‘Green’ Transition through Contemporary Art and in the introduction she writes about the Utö field trip as one of her starting points in thinking about lithium in relation to contemporary art. Later in the spring she organized a film program and a symposium at Färgfabriken in Stockholm where I was invited as one of the speakers. In the beginning of the summer I reached out to Victoria to continue our conversation and to hear some more of her thoughts around lithium, extraction practices, the so-called “green energy transition” and what, if anything, contemporary art has to offer in this context. How did she become interested in lithium in connection to contemporary art?

Since I come from Argentina, a country with the second biggest lithium reserve in the world, I have been following the topic of lithium, more specifically its extraction from salt flats, for several years. For a few years the topic has been starting to appear first on independent and then mainstream media. Even though there is much resistance to lithium exploitation in the Argentinian Andean salt flats from Indigenous communities and environmental activists, these stories of resistance are outshined by the discourse of ‘development’ in the country. Going through a deep economic crisis, Argentina needs more investment and production, and lithium appears as the magic solution that could make the country rich. It is very interesting that this ‘development’ discourse is present in most political parties, except for some left-wing politicians. While following these debates, in 2021 I had a conversation with Belgian/Australian artist Alexis Destoop, who at the time had an artist-in-residence at IASPIS in Stockholm, in which he mentioned the international collective On-Trade-Off, and also your artistic practice, both of which focused on the element lithium from different perspectives. As a curator, when I found that there were some artists in the world developing projects around lithium, it immediately sparked my interest and I wanted to know more about the intersection of contemporary art and lithium. I realized that very little had been written on this from a curatorial or art historical perspective (and nothing in Academia) which then led me to later choose this as the topic for my master thesis in the Curating Art program at Stockholm University.

You were saying that in Argentina there is quite a lot of media coverage around lithium extraction and the lithium industry, in Sweden my impression is that it is mostly written about in specialized journals on finance and/or mining. How have you experienced the public understanding around lithium in Sweden?

First off, and just as a first impression, one of the differences that caught my attention when I moved here was the great number of electric cars in use in Sweden. I had never seen an electric car in Argentina. Even though there are some, they are not that common. Suddenly I found myself in Stockholm where they were everywhere. Aside from this trivial impression, public understanding around lithium and the ‘green’ transition in Sweden and Argentina are completely opposed. When asking people that live in Stockholm what they knew of lithium, the only thing most people would say was that it was used for electric batteries of cars and scooters. When enquiring if they knew where it came from, none of them did. Of course, the people I asked were not specialized in the topic, yet if you were to ask about lithium to people in Argentina, most of them would definitely know the basic value chain of lithium, the increased prices of the element on international markets, and its strategic relevance in today's world.

This is really interesting to hear, and I have had similar experiences when talking about lithium to people in Sweden. But on the other hand, as you say electric cars are very common here and there are also several large battery factories being built at the moment, so one could think that the general knowledge would be better?

The reason why most people know about lithium in Argentina, is because it is part of the so-called “Lithium Triangle”, composed also by Bolivia and Chile. Between these three countries there is at least 65% of the world’s lithium reserves. Due to this circumstance, there have been a lot of discussions in the media on what extractive and productive models are possible and I would say that it is very clear in all of Latin America that lithium is the key to the energetic transition. In Sweden my impression is that people might know where lithium is used, but not where it comes from, since it does not happen within their borders. There is really no public understanding of all the problems of sacrifice zones generated by the speedy extraction of this material that Sweden and many countries in Europe desperately need to fulfill the goals of the European Green Deal. When I began my research in the summer of 2022, I made a search through the four biggest newspapers in Sweden for the mention of the word “lithium” and I found only one article about it in Dagens Nyheter. It was an article about the increasing prices of lithium on the market, and it discussed the great investment opportunity that this material represented.

Something that is quite striking when one starts to look into the media coverage around lithium is that one story is repeated over and over again in western media: it is the story of Lithium as the “white gold” that will replace oil and coal as fuel in the vehicles of the future. And the story is always illustrated with stunning photographs from the Andean salt flats in Argentina, Chile or Bolivia. Something white, pure, clean and beautiful to replace the black, greasy, dirty and ugly oil and coal industry while at the same time make the connection to gold and the gold rush as the original story of literally digging up treasures from the earth. It is much rarer to find stories in the media that talk about the ecological problems and social injustices that occur in and around the extraction zones or stories that try to problematize this absurd idea that we as a society could somehow mine, produce and consume ourselves out of the global climate crisis. And so while literally all of us carry around one or more lithium batteries in our pockets at all times (in our phones, earplugs, power banks, computers, tablets etc.) most people are completely unaware of the implications that lithium extraction, refinement and battery production causes around the world. During the time that you have been interested in lithium have you noticed any change in the general discourse when it comes to awareness, knowledge or interest around lithium?

Honestly, in a general discourse, no. The European Union members are still laser focused on fulfilling the goals of the European Green Deal at all cost, failing, or choosing not to bring to public attention all the problems that extraction causes on green sacrifice zones. In Argentina, discourses around lithium being the savior of the country in a context of deep economic crisis are still the protagonists of the discussion. However, on a more personal note, I have seen how information about lithium can change the way a person sees the ‘green’ transition, and that it can open up to a critical questioning of the actions of the Global North; the moral high ground where these countries stand on is unveiled. I have seen these reactions among friends and people that attended the project I did at Färgfabriken this year, more specifically the seminar that you, Henrik Ernstson, and myself performed.

For me the two things that stood out in the seminar at Färgfabriken, which is maybe also the two things that I find most alive in my own thinking around lithium is that the “new” structures around lithium extraction follow in more or less exactly the same lines as the historical colonialist and extractivist practices of the past, but at the same time and due to the ongoing climate crisis we still somehow have to do it…

I think one of the biggest challenges with lithium in the ‘green’ energy transition, is the need to change production and extraction systems as a whole. The discourse around this transition is that we will move from polluting and dirty fossil fuels, to clean, renewable energy sources. This narrative also establishes that the way ‘we’ generate new types of energies is clean. This of course is a falsehood, where traditional extractive models exploit land and racialised peoples in extraction zones, most of them in the Global South. I know that lithium-ion batteries and the ‘green’ transition are the best options to stop the exponential emission of greenhouse gasses that provoke the increasing temperatures in land and sea. However, perhaps the most challenging part is to rethink and change the production and extraction systems through which the transition would be possible. Maristella Svampa, a famous Argentinian sociologist, proposes to think of the current transition as an environmentally friendly and socially just process. She redefines the energetic transition, thinking about its potential as the eco-social transition.

![]()

This is a very interesting thought, to try to challenge the language and charge this necessary transition with other values. I have been thinking a lot around two specific perspectives on the global situation: the group that call themselves Ecomodernists and on the other hand the degrowth movement. Both of these groups agree that we have a climate crisis and that global action is necessary but they disagree on what this action should be. The Ecomodernists claim that technological solutions, including nuclear energy and carbon capture can “decouple economic growth and ecological impact” and thus “save the climate” while continuing with economic growth. The Degrowth movement, as the name suggests, makes the claim that the only way to “save the climate” is to radically reduce global production and consumption and thus enter an era of decreasing economic growth. I think that maybe one single perspective can never be enough but that we need to keep many, and sometimes contradictory thoughts in our heads at the same time. Changing what language we use to describe both the problem and the possible solutions is then probably an important and quite powerful tool.

Yes, I think this systemic change is by far the biggest challenge with lithium, but I also believe that we need to change the communication around it, understanding that while renewable energy sources are virtually inexhaustible, the materials and resources needed to build batteries and connection systems are not. Many elements and human resources are used, much water is consumed and much waste is produced in these processes. In my opinion, we need to look into degrowth models, we need to understand as a society that this planet cannot sustain the infinite growth of our species.From my perspective as an artist working with questions around lithium this is also what makes it so interesting, to make the leap from this basic element, one of the smallest molecules there is, to the global questions around our shared conditions for living on this planet. In your mind, and from your perspective as a curator, what do you think that artistic practices can contribute to larger questions of sustainability and societal change that lithium, lithium mining and batteries are connected to?

When reading about this topic for my research, it was honestly very sad and I felt extremely helpless. Once you know facts like that the battery in your phone is made from the exploitation of land and people you cannot unknow it. Reading in detail about what was happening in my country and countries in similar situations was heartbreaking. It was contemporary art that worked as a refuge for me. Knowing that some artists were critically engaging with these topics, encouraging reflections from audiences worldwide, made me feel less helpless, and part of a community that was interested in challenging the mainstream discourses around ‘green’ energies.

![]()

You wrote your thesis around lithium in contemporary art and you curated a video program, as well as a symposium on Färgfabriken based on that research. What is the next step in your practice and will you continue working with lithium as a thematic for your coming projects?

Yes, I will definitely keep working on the topic of lithium but perhaps not as specific as I have done so far. What I mean is that I might not develop exhibitions and events that only deal with lithium, but I will use it as a guiding tool to critically engage with contemporary private and public discourses. Currently I am looking into a bigger picture, researching the ‘green’ transition more broadly and extractive practices in the Global South. I am working on an exhibition that deals with these topics from the perspective of Latin American artists for Färgfabriken, in Stockholm next year.

That sounds like a great starting point for an exhibition, I am really looking forward to seeing that and to follow what you are up to and how your thoughts develop going forward. Thank you for taking the time.

***