Text by: Xiyao Chen

GOSSIPS

You don't understand music: you hear it. So hear me with your whole body.

– Clarice Lispector, Água Viva

Words are sounds transfused with unequal shadows that intersect, stalactites, lace, transfigured organ music.

– Clarice Lispector, Hour of the Star

Gossips.

Gossip lives in the stomach. It is a sensation that tirelessly follows the contoured folds and crevices of the internal organs. Moving through volumes of various sizes and temperatures so fluidly that we forget it is there most of the time. A malleable yet grounding feeling that pulses and contracts with its abundant flow of gastric acid. Unlike words that twist and bite, it is a ‘gut feeling’. Solidarity turned into discord. Gossip, etymologically, is made up of two separate words - ‘God’ and ‘sibb’(akin). The original meaning of ‘gossip’, deriving from Old English, alludes to ‘god-parent’ or companions in childbirth not limited to the midwife. Gossip later on has expanded to be synonymous with female friends. As most of the activities women were responsible for at that time were of a collective nature, assembling with their ‘gossips’, collective daily rituals were performed in rural gathering spaces. For me the word holds strong emotional connotations, signifying female friendship with no necessary derogatory connotations.

Here I am, sitting in the corner of an attic in London and gazing over the rolling grey clouds at a distance, while listening to hours of leftover field recordings on my sound card, my phone and tape recorder. Leftover, in the sense that for one reason or the other, these materials are considered to be unsuited for other projects or purposes. They are the residues left from rounds of attentive listening and sieving, no longer valuable, perhaps also known as ‘rejected materials’ in waste treatment terms… The sound piece and the text you are reading unveils the process of making sense of this material, through five chapters.

Becoming dust.

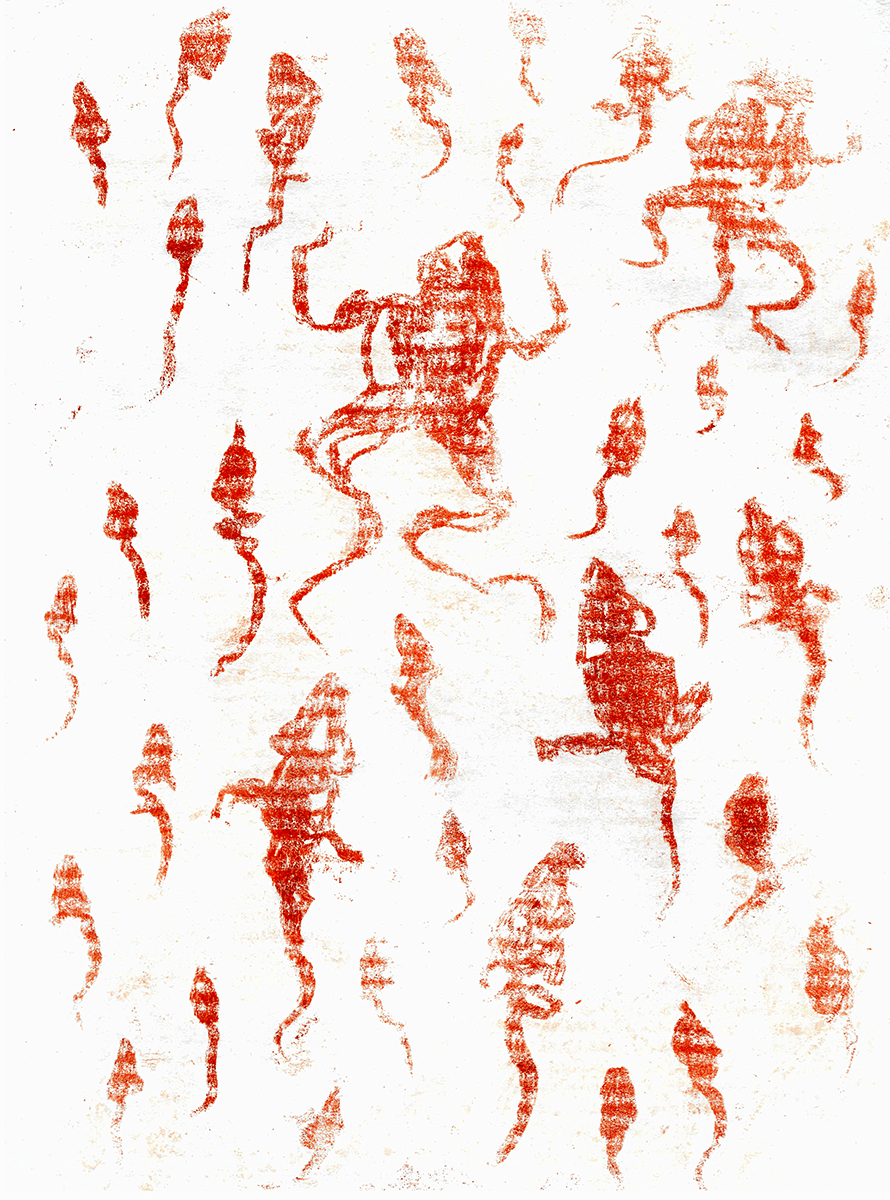

It has been raining for days, some torrential downpours transiting into reckless drizzles. No matter the intensity, it never decides to stop. Water has soaked the sky mouse grey, drenching every pore of my skin. The subtle colour change of the overcast dome obscures the hours of the day. On a swampy rice field, frogs chant a cyclical gathering every April, to greet the deceased. The banyan trees mark a place that I used to call home. A place that takes increasingly arduous efforts to return to.

At the bend of a stream, I sat down on a boulder with a group of women making ‘meeting paper’ - a sort of traditional low-grade paper made from local reeds, a carrier of gifts and messages to the other world when burnt to ashes.

Voices swirling upwards.

Cadences as charms.

Seeing ashes swirling upwards, ascending and dissolving in a spiral motion suggests the gifts have been received safely in the other world, she says, while folding the paper with gold and silver inlays into boat shaped volumes, before releasing them to the flows of air.

The unmistakable sound of grief.

The unsettling rattles disguised as heartbeats.

The cacophony of croaks continues, as the rice field sinks deeper into the darkness of the night.

‘The Great Noise’ (Det stora oväsendet).

Translation of the witch trials in Sweden 1674. Noise meaning great roars, as well as when a creature stops being itself.Here is a place. It is a hill, the path takes you through a pine forest. It is not a hill that is too difficult to climb, but larger exposed rocks form the sides at parts, decorated with blueberry plants. When you’ve climbed to the top, there is a discreet monument commemorating the killing of sixty-nine women and six men, who in the 1600's were burned alive or drowned, accused of being witches.

I have heard that two young men had pointed fingers, determining who was and who was not a witch, outside a church in the nearby village. I have heard that the hill where this mass killing took place was at the time almost at the border of what was considered Sweden. I have heard The Great Noise. I have heard that the idea of witches and what witches was, was probably imported from Europe. I have heard that cooking and cleaning was largely featured in the trial. I have heard that Kerstin had been given food of different kinds, but when she put the food in her mouth it just disappeared. I have heard how women and their housekeeping were threatening the patriarchal order of the community. A thought keeps popping up in my mind - is gossip an individual or collective experience?

Why is divination women’s duty?

The Picos.

The elders from the village refer to the room at the end of the corridor as ‘the chamber’. The convoluted corridor leading up to the chamber gets darker and narrower as one ascends. Blackened mirrors on either side reflect the dances and fights of chiaroscuro, cracking, peeling and losing their colours and glories in slow motion over the past three centuries. ‘They (witches) used to live in this valley, before they were locked in the chamber by Inquisitors’, the elders from the village laugh about this over dinner. I feel a piercing sharp pain in my stomach. We cut hay following the shadows of the waning Buck Moon. Her risings have been temperamental, both in terms of time and position. Some evenings we thought she might have missed her shift and probably wouldn’t shine on the stage of a clear night sky. Much the same as the spread of Mugwort bushes, who seem to always keep an orchard away from the chamber.

Whispers seem to travel more flowingly, in the still nights without the moon. Passing through one ear to another, the message swells and shrivels, depending on the moisture content in the air. Violence could also be aggravated by the dampened distortion of speech.

Dispossession.

It is quite an elusive process how field demises were first sketched on paper and then imposed on untamed landscapes - the plants I know of by heart tend to grow against demarcations. Overgrown hedgerow lines require laborious maintenance, either by hand or by deploying gasoline fuelled machines. Yet the landscape is forgetful and heals every spring. Reading ‘The Book of Trespass - Crossing the Lines that Divide Us’ on a stormy afternoon. The right to roam is still a hankering in rural England. The book encourages us to leave the “designated right of way” and cross the line, to ‘look inside this system and find out who put the lines there, and how’. I wonder if witch hunts would have taken place without the violent cycles of land grabs and the disintegration of communal forms of agriculture, which proceeds capital accumulation in rural Europe. I channel my eco-depression through barefoot contact with the muddy ground, as the storm moves on to the next village.

Lavatorio.

Following reverberations of the flowing water, Rippling against the bare concrete walls,

I walk in circles to greet her.

Vowels being swallowed.

Stuttering.

Slurring.

Women from the village used to gather with their gossips here,

Chatting while thumping their laundry.

Sweat and laughter stain the concrete basins.

Now behind closed gates,

The water still sings their secrets.

The same body of water is channelled to irrigate chickpea and garlic seedlings in the field.

We shall not forget,

Sowing seeds with the waxing moon.

Unfulfilled dreams planted with the waning moon.

Once again, she went to the tavern with her gossips;

Once again, she crossed the line;

Once again, she feared the darkness;

Once again, she lost her reproductive rights over her body;

Once again, she became an immigrant;

Once again, she gathered yarrow on the longest day;

Once again, she learnt how to count from one to ten in a new language;

Once, …

***