Abstract

I, we have moved.

I left Västernorrland twenty years ago. Moved abroad. To a city. To another country. Another city. To a city. Back again. Again to another city. And lately, a city that has been my home for a while.

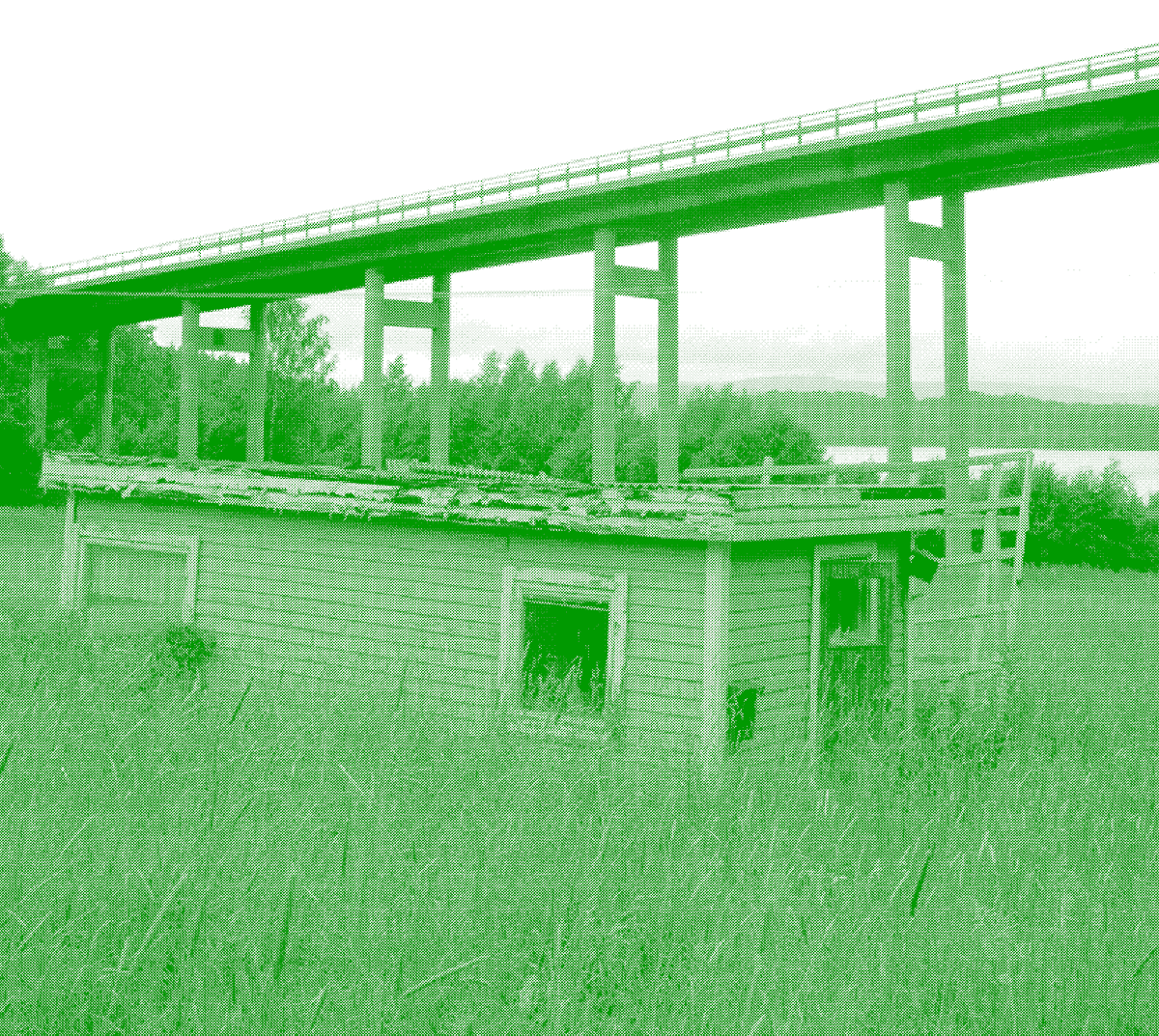

In that time, Västernorrland and other peripheral areas decreased in population. Broke down. Some even collapsed. Empty houses are ubiquitous, municipalities struggle with precarious economic situations – and public spaces have either disappeared or become overgrown, replaced by shrubland and brushwood. Highly monitored, and abundant at the same time. A sort of mix between hyperlife and decay, striving trees and closed down city centers.

In the 1970s an experiment began in Cambridge. A former four-acre farm was purchased and then left to its own devices. After 10 years a thicket of hawthorn and brambles sprang up out of the brushwood and eventually became an oak forest. One intermediate stage was the shrubland that protected the small mammals and birds that moved in. Eurasian jays, gray squirrels and others, by collecting and storing nuts and seeds in the brushwood, laid the foundation for common ash and field maple, which in turn paved the way for young oak saplings. The young trees were protected from hungry deer by the thicket. There are sometimes possibilities that have gone as yet unnoticed, but how can they be utilized for the creation of new commons and communities and not merely become growing grounds for capital accumulation. For timber trucks and machines that turn a very fine balancing act into a car wreck.

Trees, forests and fungi have the ability to break through asphalt and reclaim ground. Agaricus bitorquis has been documented breaking through ground in a brutal fashion. Japanese knotweed is the arch nemesis of UK homeowners. Weeds rise up through the cracks and start slowly reoccupying neglected parking lots.

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

Grounding and connectivity are required. At odds perhaps with an economy and society that prefers things up in the air, abstracted, temporary, just in time, disconnected. The alienated kind of living.

What happened?

In my case, we migrated. I did not think about it in those terms. It’s unusual to name it that way too. But I left. We left. Like many of our peers. Trailer packed, my parents drove. Unpacked in a city. Made a non-decision, decision. Lives of decisive non-decisions.

The blueprints of expectation in which we move.

In an artist talk in Malmö a few years ago Lisa Nyberg traced her family movements. From the inland to the coast. Similarly, my family's migration pattern mimics hers. From rural environments to urban landscapes. From my grandmother's upbringing in the countryside outside Junsele. Farmers. To my mother’s childhood along the river in Liden. Foresters. To the youth of my sister and me in the coastal town of Härnösand. Builders and administrators. To my own daughter’s life in Stockholm. Artists and dancers. The movement. A copy of Sweden’s changing economy. From rural manual labor to urban economy. At least a copy of how Swedish politicians liked to think about it.

Life in abstraction. Work in alienation. Art in the abstract. Within each product there is labor that disappears.

The processes of the forest: winding tree trunks, seeding pine cones, networks of mycelium between trees and fungi; plus the chainsaws, computerized timber machines and the workers produce the lumber industry, and the floor at my feet.

Manufacturing in China, cobalt mining, processes of fermentation and industrial-scale roasting combine with myriad other production lines to produce me here today, drinking coffee in a café and writing these words on the device in front of me. Words that are then stored in online clouds in northern Sweden’s server halls. Nearby, a few months ago, LKAB announced the discovery of Europe’s largest deposit of rare earth metals, in the Kiruna area. This labor is all-encompassing. It surrounds us, but it largely cannot be seen. It is spectral, but it haunts.

Work then is abstracted from living. Everyday life. The same with the infrastructures that make life possible. Integral components of absolutely everything, definitely there, but at the same time not. I plug into the power. It works. I am not sure how exactly. I turn on the vacuum cleaner and the dust disappears from my Miljonprogram linoleum flooring.

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

In Summer 2013 we drove back home. We took my parents' car. Keeping to the coast. Driving over the old bridge prior to the completion of the Höga Kusten bridge.

I remember being 14 and standing at the top of it, with friends. We were on a school trip. I remember the anxieties and insecurities. Haircut. Body. I also recall a strong feeling. A trust that I was going places. I was not going to end up here. I was moving. Exploring. We stood up there. We peed to see if we could reach the water far below.

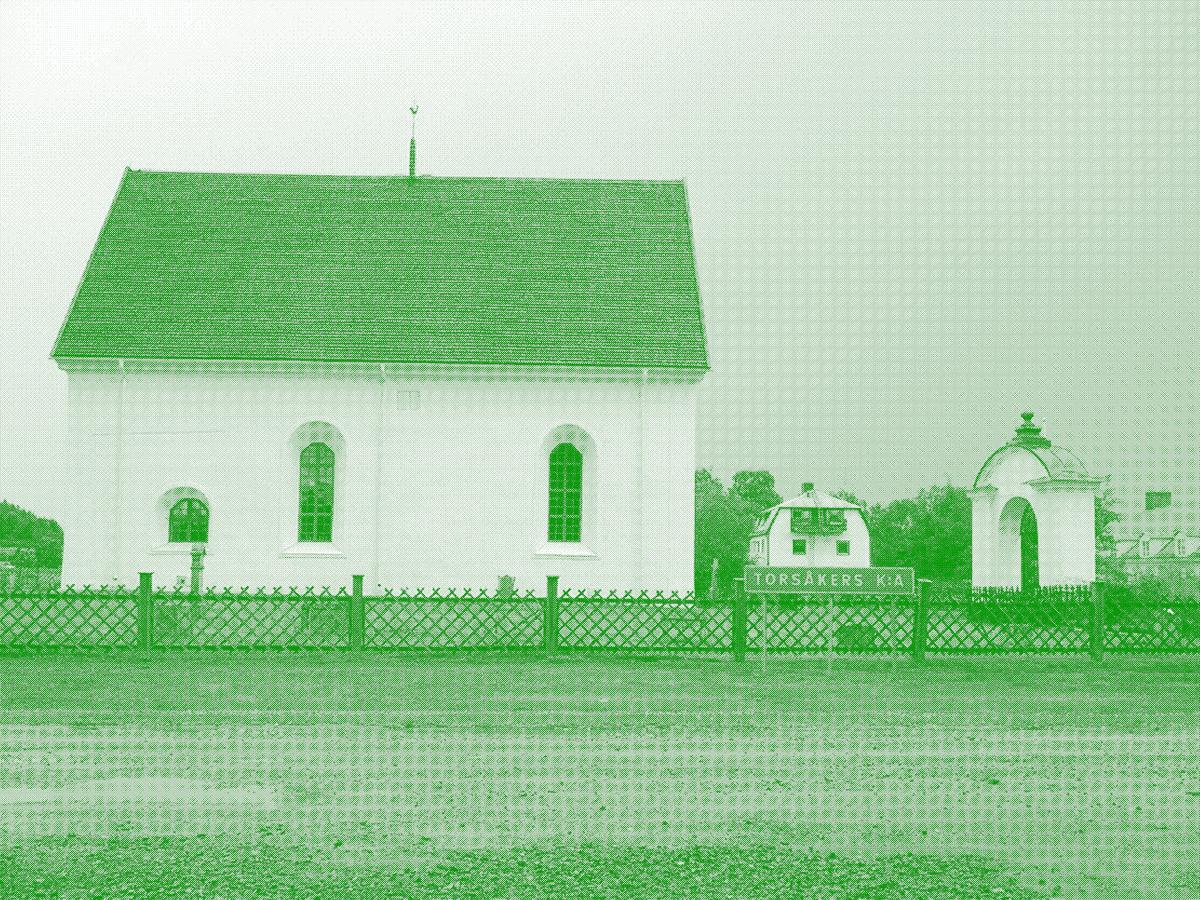

I parked the car and sat down in the grass. We had moved. And moved again. This time back to Sweden. To Stockholm. I had just finished Konstfack. I was looking for context. For grounding. That could link me to the soil beneath my feet. We climbed a small hill that day. Reaching the top through a windling natural landscape. Feeling the pine tree root system under the soles of my Nikes. I remember reaching the spot we had planned to visit. A place where sixty-nine women and six men were burned alive or drowned. Accused of being witches. A nature spot. A supernatural spot. It is the biggest mass-killing in Sweden during peacetime. Two young men were pointing fingers and determining who was and who was not a witch outside a church in Torsåker. A village named after a god from Nordic mythology, Tor. Thor, god of electricity, and his åker, or field.

Christianity established itself first in cities; an indoor, urban religion. It was at an altar in a protected, walled-off stone church, in the city center, where people could meet the new religion’s god of the sky.

In 1674 there was a population shift, from the countryside to the towns and villages with a church. From the landscape to the urban center. A milestone in the process of urbanizing nature. Churches in the center, bells to keep the animals away.

We walk down. We drive on and pass a house. A large red house where my 16-year-old self and my father sanded the floors one summer. It is a nice memory. A memory where I learned to love floor-laying, the trade of my father. The house is an old wooden former school building in the middle of the forest. That was my first job. I loved working for my dad. It was a weird way to direct my energy on something tangible. Getting rid of nails, linoleum, and all the other crap that had been walked on by generations of people. The school is now a private home. The classrooms have become master bedrooms. The kitchen, once a small labyrinth navigated by generations of kitchen workers, has become an open-plan living room. A place built for communal learning is now a place of individual being. A microcosm of the transformations in Sweden.

It is a dear memory. Especially as my Dad has passed on. Today, I wear the socks he produced as a fun giveaway accompaniment for his clients and friends. The company name was printed at the bottom and there were tiled squares at the top. The idea was that once a floor was done you only needed socks when walking across it. No nails in the floor, no shoes needed. The flooring of this place remains. The labor that created it is still etched into the floor-boards. It supported the movement of people in the past, and continues to do so in the present, but what is still to come? What role might this ground play in the future? Between the now spectral hands that made, sanded and cleared it, to the feet of those specters still to come. What comes next after this fleeting phase of individual being?

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

Five years ago few politicians or news channels were reporting on the north of Sweden. Today, large media companies reopen editorial offices in the north. Politicians are again speaking about the region as the land of the future – echoing language last heard more than a hundred years ago. Returning seems to necessitate industrializing. The green future and the sustainable society – the north is to take on the lead role, at least according to the Swedish government. At least if the communities that have lived there for generations can be silenced and ignored.

Returning, I watch. I see my home, my village, my house. Less populated, more exploited. I see the dissonance between driving the electric car and the wasted ground of a mine. I see the landscape of wind turbines that threatens livelihoods of the Sami community.

Returning to the street with the closed-down book store, the cafés that cease to exist, the unwalked floors, the empty shop windows.

Returning, alone and together. Returning to a landscape with a newfound interest and capital to match. Returning to the same exploitations. Returning to the same form, reimagined. The same harvest forests. The same dead falls.

Listen.

***